This post is part of a complete, open-source resource document called Marketing For People Who Hate Marketing.

The Problems With The Common Funnel Approach

Ah, yes, the funnel. If you’ve ever googled “marketing” or hired a marketer, you’ll witness this image.

I’m not saying that all models are perfect, but before you accept this one as your guiding light, you’ll need to know what it’s good at and what it might accidentally do to your business.

For the record, all of this is paraphrased from the book “How Clients Buy” by Doug McMakin and Doug Fletcher. This is the shorthand version, so go read the book if you need more detail.

Problem 1: The funnel assumes infinite leads

The funnel is an okay proxy if you’re selling $15 iPhone cases, $7 bars of soap, or candy bars for $1.50 at the impulse checkout aisle. For the most part, iPhones change and people want new cases pretty regularly. Soap and candy are both consumable and can disappear pretty quick. So even though the world is made of a finite number of people, the funnel works okay for these types of sales.

On the other hand, if you’re selling 4-5 figure contracts, logos, or other creative work, you’re in for a surprise. You’re working with what’s known as a niche market. This means that you’re not selling to everyone who owns a wallet. You’re selling to a very specific, narrow type of person or company. You may feel strongly that “our product is for everyone!” Unfortunately, as discussed in Chapter 1, that’s just not true.

The funnel assumes that you’re going to acquire a new customer and then let them go at the end of the transaction. This is bad news if you have a high customer acquisition cost.

Here’s the most advanced math you’re going to see in this document:

CAC < LCV = Growth

If your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), which is how much it costs you to find and sell to a new customer, is less than the total Lifetime Customer Value (LCV), your business will grow.

Loose paraphrasing from Seth Godin’s Startup School Podcast:

Every time Starbucks opens a new coffee shop, they know that they’re going to create thousands of new coffee addicts. This means they can spend a lot of money giving away free coffee and other promotional products just to get people in the door. Once they do this, their customers come back many times per month.

Years ago, some executives in the airline industry figured out how to increase their LCV in order to balance this equation. They figured out that if they made up this concept called “airline miles” their customers would stay loyal to them, even if the flight cost them more. The points cost the airline nothing to make, but customers felt like they were missing out if they didn’t stick with their airline. They didn’t have to figure out how to spend less acquiring customers because their retention helped them increase LCV, which allowed them to continue growing.

The bottom line:

Leads are not infinite. They do not appear from nowhere. They are people who are connected to other people through a broad network called “relationships.” When you set your marketing campaign up with a funnel as the meter, you will slowly forget this. I promise.

Problem 2: The funnel assumes a short conversion time

Just look from top to bottom of any funnel diagram, there are usually only a few steps. The funnel shows phases but has no axis of time. It doesn’t show mindset or decision-making, and it certainly doesn’t show what the customer needs at each step–only what you need.

If you’re selling Pop-Sockets on an e-commerce site, you probably can get away with a relatively short funnel. It’s not that hard to build trust, just show some product reviews, a few badges that say “certified seller,” or a Paypal sticker that proves you’re legit. You can even create a return policy that helps new customers feel like purchasing from you is less risky–but your customer probably isn’t going to belabor about which Pop-Socket is best for them, since the total risk to them is probably less than $10.

For anything else, building trust takes time. Building a relationship takes time.

For many service businesses, a conversion may take months or years from start to finish. Here’s an example:

A candidate client searches the term “company retreat facilitator” on Google. They find a bunch of resources on how to do it themselves by reading a helpful blog post. After trying to run a retreat themselves, the client realizes they need more help, so they hire internally to take on the new responsibility. That new hire reads a book, takes an online class, and sets up the next year’s retreat. Everything goes well, thanks to the resources they’ve been following. Finally, the client realizes they need to take their retreat to the next level and finds your video on YouTube. They look at your website and decide to reach out for a quote. When we look back, we find that it was your blog post that initially helped them with their first few retreats–which helped them trust you more when they met you in-person.

This is a multi-year timeline that slowly, slowly build up trust. On your side, it took a lot to create all of those resources as part of your inbound content marketing strategy and it was frustrating when all you got was views and likes and no new clients–but eventually, the client found you.

Problem 3: Assumes if you can measure it, you should

This is a problem for marketers, but it happens everywhere else, too. In fact, I’ve seen this most commonly in the “productivity” space, where task management apps like Asana or Trello will track the number of tasks your team completes to help you approximate how productive you are.

Well, obviously, not all tasks are created equally. Writing an email to “set up a meeting” might be a task on your team’s to-do list, but if it sits alongside “create marketing plan,” well that’s just not a fair comparison. Those tasks are different sizes. Your metrics are B.S. You’re so much better off not measuring any tasks at all and finding something more meaningful to measure.

I’m now going to tell you something so embarrassing about the marketing industry that your’e going to wonder if I’m even telling the truth because it seems so silly.

Have you ever gotten a pop-up advertisement on your phone? Have you noticed how some ads will hide the “x” (the one that closes the ad window) from you? It might take you a second to find it, because some ad engineer was being graded by their boss on the metric of “how long do people look at our ads?” They make the foolish assumption that if someone looks at the ad longer, they must be doing it because the ad is interesting and they are more likely to click on it.

I know, I know, you’re sitting there thinking “this can’t possible be true, it’s so dumb, how could they not know?” I promise you it’s true, and it’s not because they don’t know, it’s because they’re measuring the wrong thing. It’s the same reason they made that little “x” smaller and smaller over the years. They found out that their click-through rate went up when they made the “x” smaller.

How does that make you feel as a customer? Does that ad engineer understand you? Do you feel like they are trying to help you solve a problem? Or does that ad make you want to light your phone on fire and throw it into a ceiling fan?

It’s not stupid. It’s human. When we grade ourselves on an axis, we want to see the numbers go up and to the right. It’s very, very normal–but when we pick the wrong axis or we simplify complex behavior into a single number, we lose so much. We lose too much. It’s unacceptable to subject customers to this.

Make sure what you’re measuring really matters. If you’re not sure or if you got the metric from somewhere else without studying why you’re measuring it, forget it. You will be better off measuring fewer things, I promise.

Problem 4: Does not account for referrals

Let’s keep rolling with that last example about the pop-up ads. Let’s say it was a local HVAC company who served you the ad. The next time you see their logo, how will you feel? You’ll feel like they treated you poorly and that they don’t understand you. There is just no way you’d give them your money, especially if it continues to happen.

What’s worse is that this HVAC company also cannot see the story you might tell others when they ask you about your experience.

The funnel is linear and assumes that everyone entering is doing so through the top, where they’ve never heard of you before. It also doesn’t encourage the sales people to follow up with customers after the sale to ensure that the story they're telling others is positive. The funnel just dumps customers out after they have a receipt, with an occasional ask for a review or rating.

The funnel doesn’t account for how customers interact with other leads and the funnel doesn’t account for return customers.

In the SaaS (software as a service) model, typically, the biggest problem is known as “churn.” This is just the rate at which users of the software are leaving the platform. When your life blood is “how many users do we have this month?” you need to pay attention to keeping them onboard. The problem usually isn’t another app or that your software doesn’t solve their problem, usually, the problem is that the app forgot to make it social.

Without direct messages, hashtags, or geotags, no one would care about Instagram. Instagram works because your friends are on it, too.

Problem 5: Assumes a linear buying journey

Think of the last time you bought a car. Did you realize you needed a new car, walk into a car dealership, get a test drive, negotiate the price, and then walk off with the car?

Probably not. Instead, you probably did a lot of reading about what car you need and what new models are available now. You may go out to test drive the Toyota Highlander but then realize that you need the AWD that the Subaru Forester has. You might go back and forth on which trim you really need, or which dealer you want to work with. You might even have an Uncle who has a shop who can give you some insider tips.

For small price, low risk items, the funnel mostly works–but if your product or service requires more trust or time, your lead may go up, down, in, or even out of the funnel completely.

The funnel just doesn’t map to the reality of the buying journey and it doesn’t encourage the marketer to think about the lead as a person with unique situations that may be pulling them in or out of flux.

I used to work with a large client called the U.S. Government. Yes, they were huge. During that time, there were multiple occasions where the client understood what we were selling and wanted it–but couldn’t purchase. Sometimes it was because of a billing cycle. Sometimes it was because of a new higher-level approval process. One time, we found out that if we priced our product at exactly $1999 instead of $2250 we were suddenly able to sell it–because the limit on the purchasing authority for the buyer’s company card was $2000.

You don’t know what might influence your lead to move from ready-to-buy to not-ready-to-buy. Your job is to listen and figure out how to solve their problems. If you do this consistently, you will build trust and rapport that you might cash in for a contract later.

Problem 6: Perpetuates the myth of the super-salesperson

Most sales environments are set up to be “rah rah,” “go get ‘em buddy” teams. The idea of management is that if we create the right incentive and competition, the team will push each other to excel. In sales environments like this, only one number matters and that’s money.

Banks are particularly well known for closely associating a monetary value to each employee, labeling them precisely what they are worth to the company.

The funnel is the perfect tool for this because it’s very simple, very linear, and very easy to ruminate on a single output: sales.

This means that sales teams look for competitive people instead of collaborative people. It means they would rather hire a football player because “they know how to work hard” instead of an engineer or an analyst who doesn’t have overt charisma in an interview. I’m not saying hard work isn’t valuable or that football players aren’t amazing sales people–I’m saying that homogeneity is one of those things that feels like a good idea when it’s happening and then creates a problem that no one predicted.

This is one of the biggest problems with sales teams and it’s largely responsible for why so many of us associate sales with pushy, non-helpful sales people. The funnel allows an individual sales person to walk a customer over the finish line, giving all the credit to the “closer” who made it happen. It doesn’t take into account all the other work that might have been done by other members of the team, or the possibility that the lead already knew what they wanted when they walked in the door.

Let me be very clear about something:

Competition can be healthy, but when you’re keeping information private or actively hoping that someone else on another team does poorly because you’ll get a bigger cut, it is unhealthy. This is not a sustainable work environment and the main symptom that reveals this toxicity is sales person turnover. When an employee doesn’t feel like the company has their back or cares about them as a person, they will reserve no loyalty and will leave at the first sign of a better work environment, or better pay (a more common proxy).

What we know about motivation is simple to understand, people work just hard enough to get the carrot or just hard enough to avoid the stick. The funnel creates a singular focus that encourages sales people to work in discrete silos instead of collaborating. It leaves less room for intrinsic motivation, that comes from all that fluffy, foo foo stuff like caring about others and trying to help someone actually solve their problem.

Could you imagine a world where people just wanted to help each other solve problems? I can’t.

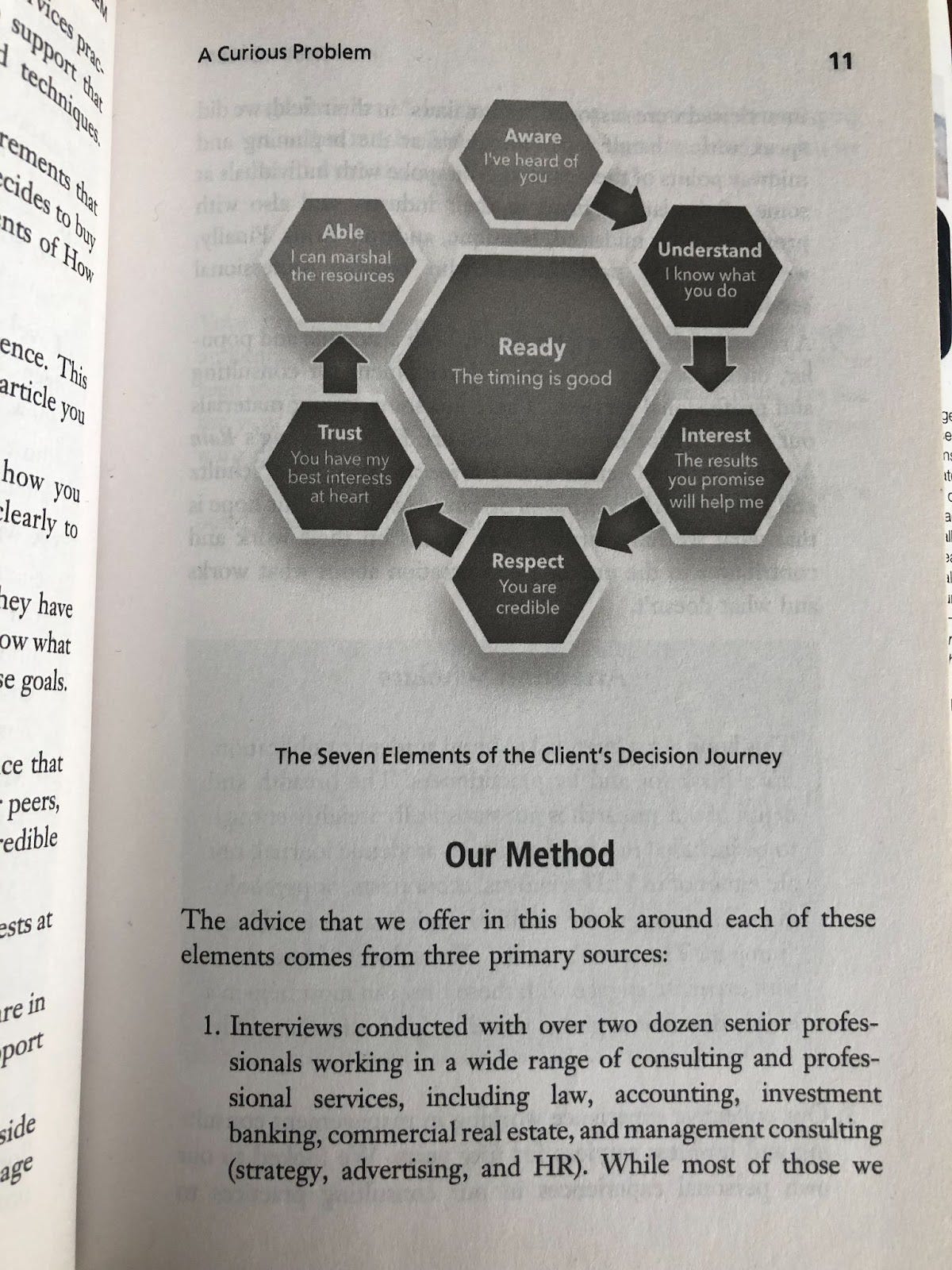

A better solution to the funnel was proposed in “How Clients Buy” by Tom McMakin and Doug Fletcher.

The Seven Elements of the Client’s Decision Journey

from “How Clients Buy” by Tom McMakin and Doug Fletcher

In this model, a lead moves between tiles that circumnavigate one central tile. It feels more like a board game, where the pieces move on top of each space. The idea here is that a client may be in any of these states. It’s your job to learn which state they’re in and how to help them. At any point, the lead could move up, back, or to a position where they are ready to buy from you. The arrows provide guidance for the marketer, but they don’t prescribe a path like the closed funnel where a lead presumably couldn’t exit–because they sure can.

This seems like a much more realistic approach that asks questions and helps you understand what’s happening in the lead’s mind, rather than looking at them as a number to be converted.

Chapter 3 Recap:

The Funnel is a poor model to use because it:

Assumes infinite leads

Assumes short conversion time

Assumes if you can measure it, you should

Does not account for referrals

Assumes linear buying journey

Perpetuates myth of super-salesperson

NEXT UP - Chapter 4 - Aligning Your Strategy With Your Values

The truth about values assessments and maintaining integrity between actions and values.

What is Antipattern Media?

Antipattern Media is a creative agency the helps social-impact driven businesses grow their triple bottom line.

We believe in “mixed martial media,” which is the use unconventional, multidisciplinary techniques from old school direct response marketing to guerrilla marketing to community development to modern digital advertising.

Unlike most creative agencies, we combine outside-the-box thinking with real, measurable outcomes you can trust, like “return on ad spend” (ROAS).

Ways to engage us:

Diagnostic Report & Roadmap - We’ll run our multi-point diagnostic and provide you with a roadmap for growth.

Fixed Scope Project - We’ll scope a project with a specific outcome to a deadline and budget that works.

Retainer - After we run the diagnostic and create your custom roadmap, we’ll execute for you. We will be the functioning marketing arm of your business.

Engage with Antipattern Media: